I began with a simple plan: Get as far away from the city as possible and spend two weeks exploring a side of South Korea few outsiders experience. I bought a ticket on the KTX, one of the world’s fastest trains, and charted a course south toward the cultural core of northeast Asia’s oldest civilisation.

Seokguram Grotto is a holy place and now I’m holed up in it. I hitched, huffed and hiked out this way in the early hours to bask in the beauty of nature, cleanse my soul of the misgivings of Seoul and watch the sun rise. I came to see the understated side of the Land of the Morning Calm, but hours after it should have appeared I’m still waiting for the sun’s grand entrance.

Legends abound on the history of this ancient precipice. The most inspiring suggest that during the summer solstice when the light is right and the stars are aligned, the sun reflects off the Buddha’s third eye and illuminates the tomb of King Munmu in the East Sea. Munmu’s tomb protects Korea from Japanese invaders, the Buddha protects the tomb and a security guard protects the Buddha. With fables in my mind, I sit and watch the thunder clouds move from peak to peak, delivering their payload with unabated enthusiasm. I’m suddenly jealous of friends fond of the meditative life. Here I am in a place where serenity reigns, and all I can think of is moving on and exploring the countryside.

In the gloomy mid-morning, I return from the Seokguram Grotto and make my way to Bulguksa Temple, South Korea’s most venerated national treasure. This working temple is an architectural masterwork, an eighth-century stroke of Silla kingdom genius. Bulguksa contains no fewer than six designated national treasures, including the stone Dabotap and the simple Seokgatap pagodas. Even to an outsider, the beauty of these pagodas is every bit as stunning as better-known temples in neighbouring China and Japan. But unlike Beijing’s Forbidden City, a visit to Bulguksa means you don’t have to fight your way through thousands of camera-toting tourists.

Bulguksa’s walls don’t just drip with history – they are the foundation of history itself. Construction started on the temple as far back as the year 751. This is the Korea that existed before glass and granite. It’s a side of the country I didn’t know existed until now. International travellers flock to the Great Wall of China, smoky warrens of Hong Kong and the temple gardens of Japan. Yet locals know that this is a place worth visiting, and they arrive ready to pay their respects in the shadow of the Toham Mountain among ancient relics.

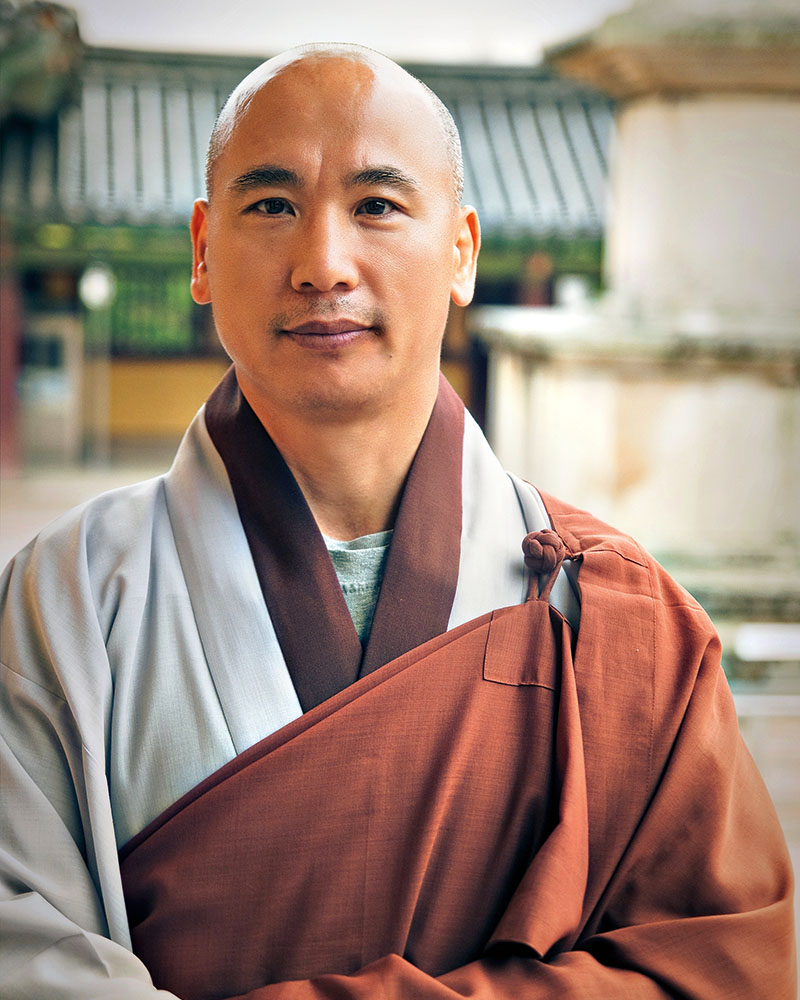

Wandering the grounds at Bulguksa in the pouring rain I’m joined by a monk wrapped in neat mahogany hues and clean shades of grey, a small umbrella balanced delicately over his shoulder. He squeezes some of the water from my dripping sweater, shifts his umbrella from his shoulder to mine and says something that, I guess, could be translated as ‘you smell as though you have been bathing in spoiled kimchi’. He invites me into his chambers for tea and offers me a chance to dry out my clothes. I disrobe and sit cross-legged on a straw mat in nothing but soggy underwear, and accept a cup of steaming green tea. Anywhere else in the world this would seem awkward – embarrassing, even – yet here I’m perfectly content, engaged in conversation. The monk recounts bits and pieces of 5,000 years of antiquity, wrapping my mind in the rich, multilayered tapestry of Gyeongju City.

I’m told about the power of the lotus motif, why gold leaf is edible and what a monk does on vacation. Yet for all the time we spend together, I am affected most by what the monk tells me about travel. “The further you go from Seoul,” he says, “the closer you get to the heart of the country. But you can’t get there alone.” He suggests I visit nearby Busan, to see how history has informed the Korea of today.

The mosaic port city of Busan is a place where decadence and eclecticism mix in unexpected ways. Busan is host to the annual Busan film festival, and home to the global shipping industry’s fifth-largest port, earth’s third-tallest building and the largest department store in the world. This is also a city known for its nightlife, world-class museums, fine dining and proximity to nature. Busan has more layers than an onion, but if you don’t know how to cut into it, it can leave you sobbing. So I turn to a friend for help.

Nathan is an American photojournalist based in Japan, and he’s been around the block. Travelling with Nathan is like dumping a bee hive into your trousers and rolling down a hill: certainly dangerous, but always entertaining. He agrees to meet me in Busan.

I exit the human pinball machine that is Busan Station and make a run for Haeundae Beach, the city’s biggest tourist attraction and a place that can make an overnight millionaire of a sun umbrella salesman.

Nathan is waiting for me, standing out among the crowds in his beige trousers, horn-rimmed glasses and with his battered satchel. “Where do we start?” I ask, pulling my guidebook from my bag. Nathan takes the guidebook from my hands and shoves it deep into his satchel. “Forget it. We’re going to rewrite the book on Busan,” he says.

Our first stop is Busan’s Russian Quarter. Tourists know it as an atmospheric place for a stroll and a great place to find a deal on swag, but locals know better. After dark, the streets here become a labyrinth of pleasure shops; a place where roughnecks from all over the world and sailors from the Korean corps come to blow off steam. I can’t think of a stranger way to spend our time in Korea, so I ask Nathan what we’re doing here.

“We’re getting real travel advice,” Nathan says, accepting an invitation into an uninviting bar.

Two beers are procured for us by an elderly Russian lady. “First you drink,” she says, allowing whatever it is she intends us to do next to hang in the air between us.

Two girls enter from the back room, though between them they’re only wearing enough clothing for one person. One is blonde. Her name is Sasha. The other is blonder. Her name is Nikki. Immigrants from Vladivostok, they’ve been living in Busan for the better part of seven years. “Skip the beach. Everyone goes to the beach,” Nikki says. “And everyone goes at the same time. If you want to see the real side of Busan, you start right here.” Nathan whispers something to Nikki, and Nikki whispers back. I grow increasingly uncomfortable. Sasha reaches into a drawer and comes out with a map and a pen. “You tell your guide book to call me the next time they need an itinerary,” she says, scribbling notes for us. “We are Busan’s best travel agency.” Sasha hands over the map marked with her notes and the girls wave us goodbye.

When my heart stops racing I ask Nathan why he brought me down here in the first place. “We could have got that information anywhere,” I say. “Of course we could have,” Nathan says. “But then I wouldn’t have got to see you squirm. Besides, I knew they’d be able to tell us where to go for dinner.” We end up in a small Russian restaurant and spend the rest of the night feasting on pierogi and alternating between shots of vodka and soju while rubbing shoulders with roughnecks and Busan’s party crowd, folks that know the Russian Quarter as one of the best places in town to eat, party and play. To say that I don’t have a great time would be a lie, even if Nathan did get my goat. I ask what else the girls put on our itinerary. “Tomorrow morning we’re going to the fish market,” Nathan says. “But we’ve got to be there early.” Busan’s fish market is one of the largest in all of East Asia, and a great sensory delight. Sasha has told us which vendors sell the freshest mussels, where to find good grouper and how to tell a good blowfish from a bad one. By 7am we’ve met half of the merchants, spent some time on the shipping docks and taken our fresh haul up to the second floor of the market to be cooked in front of our eyes. Between bites of fish, Nathan looks up at me and smiles. “Not a bad way to start our tour,” he says. “We can catch a cargo ship to Russia if we hurry.”

Reluctantly, we leave Busan behind and depart for our next destination. We ramble up and over the waves of green at the Boseong Tea Fields before charting a course to the island stronghold that is Ulleung Island. We scratch our heads at the sight of the Gochang Dolmen – a quizzical landscape of 35,000 Bronze Age stone burial markers – before heading for the northern border and the Seorak Mountain Range, the location of our final pilgrimage.

Nothing stirs the national spirit of South Korea like trekking. We decide to get in on the fun and see the sunset from the pinnacle of Seorak Mountain, a granite kingpin that towers over the Sea of Japan, the mysterious hills of nearby North Korea and the picturesque seaside village of Sokcho. We meet all manner of folk coming off the mountain as we begin our ascent, their spirits enlivened by the mountain air, each eager to paint us a picture of what is to come. Halfway to the summit we join a large family for a barbecue. It’s not uncommon to see a portable gas grill and two pounds of fresh pork stuffed into a backpack in the mountains. Later we catch up with a pair of brothers from down the coast and share a bottle of Korea’s ubiquitous national spirit, soju, a distilled beverage commonly compared to vodka. A good day of trekking begins and ends with libation, according to a contemporary Korean proverb. The day wanes as we climb and darkness encroaches. The soju and the crisp mountain air cleared my mind, and I’m wondering if this dark ascent is a good idea. Nathan tells me not to worry.

We make the summit at Daechongbong Peak in a driving wind that threatens to blow us into the valley below. We’re alone now, gazing out over this very alien moonscape, the craggy mountain awash in soft blue light, with squid boats lighting the horizon like an infinite army of stars. Standing among the storm clouds is as much a metaphor as it is a moment.

South Korea is a beguiling and charming nation that reveals itself to travellers in bits and pieces. Korea’s traditionalist dignity, amiable locals and futuristic outlook have thrilled me, surprised me and grown on me. Staring out the window on my train bound for Seoul I can’t help but reflect back on these two weeks fondly. I’ve felt at home here, and understand now what the great wordsmith Robert Haas meant when he said: “Korea becomes a synonym for life”.

Get there

Get there

Korean Air offers daily flights to Seoul from Brisbane.

koreanair.com

Stay there

Stay there

The Lotte Hotel Busan has the city’s best sea and city views. The hotel can arrange walking tours of Busan as well as onward transportation to Gyeongju.

lottehotel.com

Get inforMed

Get inforMed

Try Robert Koehler’s series of insightful guidebooks, published by Seoul Selection.

seoulselection.com