As I climbed into my hammock I ran through the checklist of safety measures that, after a week trekking through the Darien jungle, was becoming almost a routine.

My hammock was tied high enough to allow jaguars, pumas and caiman to pass underneath. All our packs were likewise suspended from the branches to make them less attractive homes for the dreaded fer de lance snakes. Suspended as we were from the trees, it would even be possible for one of the hundred-strong herds of killer wild pigs that inhabit this jungle to pass unhindered through the camp. My mossie-net was well sealed to keep out the mosquitoes, the real terror of one of the world’s worst malarial regions. With luck, the thick fabric of my jungle hammock would even provide some protection in case of attack by unpredictable Africanised bees. I had sprayed the hammock strings with industrial strength DEET to deter scorpions, spiders, red ants and (I hoped) snakes. Lanterns had been hung up around the camp to keep vampire bats at bay. I was uncomfortably aware, however, that these lights could also reveal our position to guerrillas, paramilitaries, drug traffickers and sundry ne’er-do-wells who inhabited this area. There are many reasons why Panama’s Darien Gap is often described as the most dangerous place on earth.

Over the centuries, many adventurers have attempted to explore this mysterious wilderness. The vast majority fell foul of what became known as the ‘curse of the Darien.’ It took just over a year for the Darien fevers to wipe out one colony of over 2,000 Scottish settlers. In 1854, an American military expedition set out to cross the 80-odd kilometres that lie between the Caribbean and the Pacific coasts of Panama. In the 74 days that they were lost in the jungle, several died and many were driven to the brink of cannibalism.

We had come here to try to retrace as closely as possible the route of conquistador Nuñez de Balboa when he marched across the isthmus in 1513 to become the first Westerner ever to set eyes on the Pacific coast of the Americas. In researching this expedition, it soon became obvious that the few successful expeditions that had achieved their aims with at least a minimum of suffering had one thing in common: they relied on experienced local guides and hunters.

As I lay in my hammock I could hear the reassuring chatter of three Kuna Indian expedition members from where they sat around the glowing campfire. A shaman with the unlikely name of Teddy Cooper was their leader. Many of the Kuna from Teddy’s island in the San Blas archipelago found work in the American Canal Zone, and a trend developed of adopting whatever names caught their imagination. Our porters were the brothers Mellington and Rommelin Merry. On one memorable evening back in San Blas when we were preparing the expedition, I drank beer with Bill Clinton and a young lady called John F Kennedy.

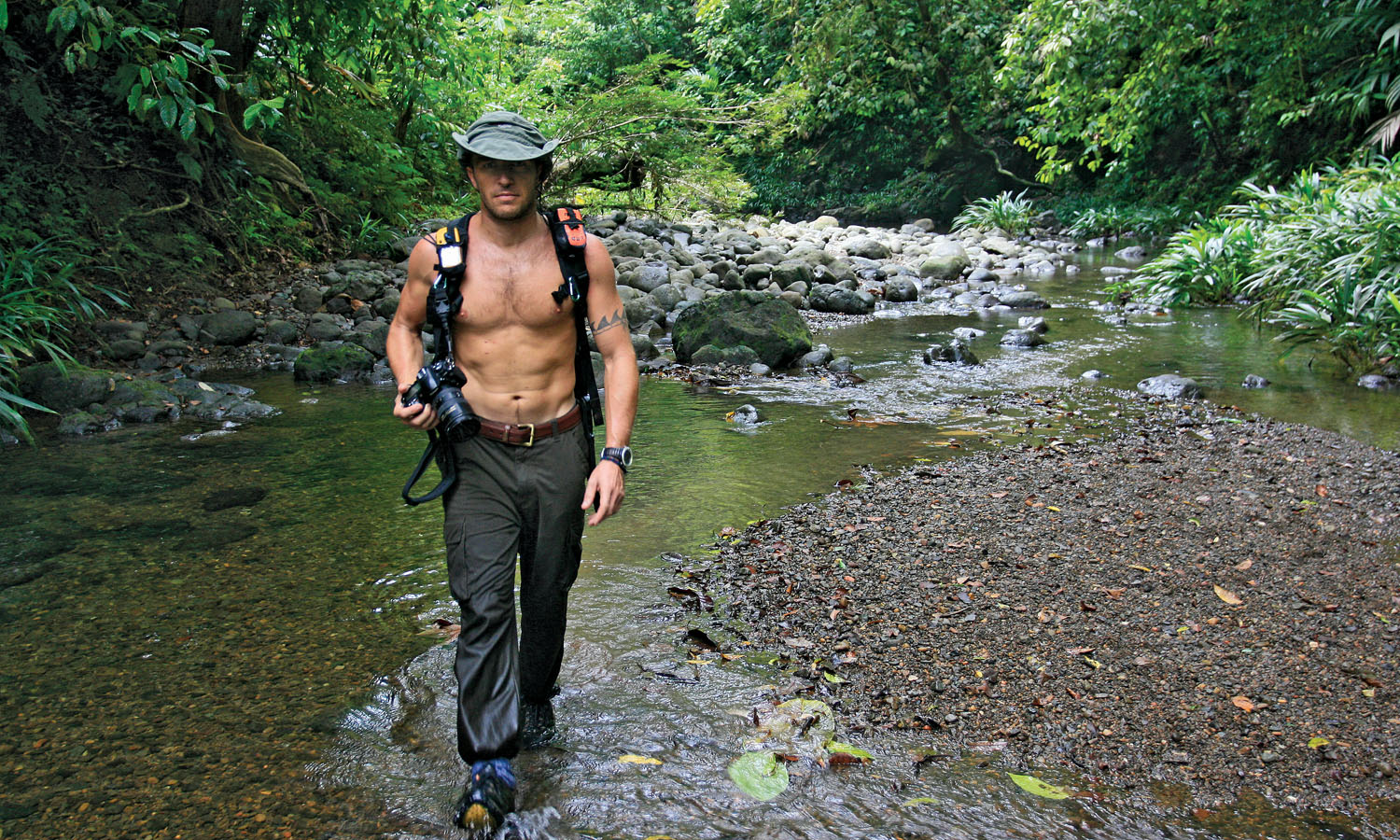

The stalwart amongst our porters was Berto, a Panamanian from farther up the Caribbean coast. He was already snoring in his hammock next to Jose Angel Murrillo, a well-known Panamanian photographer and one of the most experienced Darien explorers alive. Angel was the local mastermind behind an expedition that I had been planning with American explorers Jud Traphagen and Dave Demers for almost a year. Jud and ‘D-bar’ were now similarly locked away in their carefully sealed hammocks.

Apart from the advantage of being close to water for cooking and washing, riverbanks are less than ideal campsites. They attract insects and are the preferred habitat of snakes, including the fer de lance, which can kill with a single bite in a matter of minutes. Yet the Kuna infinitely prefer to take their chances here rather than sleep on the hilltops, which are believed to be the domain of a far more terrifying creature. “The boachu is like a flying dragon with the head of a jaguar,” Teddy Cooper explained as we made the long climb over the Sierra de Darien. “It takes its prey up onto hills to eat it. This is why we Kuna always pass as quickly as possible over the mountains. A man from my village was killed by a boachu a couple of years ago… someone saw what happened to him in a dream.”

For some reason it seems that the indigenous people of Darien have seen fit to populate what is already the most dangerous jungle in the world with all sorts of supernatural beasts and jai (spirits). They talk of the Madre de Agua who lives under whirlpools where she can drown passers-by, and of the Arripada, a monster with one hand shaped like a hook for tearing the heart out of its victims. The most bizarre tale is the old witch known as Tuluvieja whose sieve-like face is so ugly that she wears her long hair over her face in shame. She also has a single sagging, distended breast that hangs down in front of her. The local people say that she steals children, and when their fathers come to rescue them the witch sprays the way with slippery milk from this unsightly appendage to make it impassable.

Before entering the most remote and most feared section of the Darien, Teddy Cooper – as spiritual leader of our expedition – insisted on painting all our faces with bright red achote juice. “Now the spirits will know that we come in peace and that we are here to treat the jungle with respect,” he explained. Teddy made a point always to ask permission of the jai before hunting or even before picking plants.

The jungle tribes of the Darien also paint their babies blue when they are about three weeks old. The blue stain of the jagua plant lasts a few weeks and is said to protect the baby from spirits and curses. It probably also provides some protection against insect bites. Throughout their lives the people of the Embera and Wounaan tribes also use this jagua body-paint on ceremonial occasions, and girls are entirely painted at puberty and before marriage. These rainforest tribes are culturally far removed from the Kuna of San Blas. While Wounaan women traditionally wear just a short sarong and traditionally go topless, the Kuna women dress in fantastically bright costumes. Their fine hand-embroidered mola blouses contrast brilliantly with their headscarfs and bead-covered legs. The Kuna people are relatively wealthy and even today the women are frequently decked out in the gold jewellery (and with the typical gold nose ring) that inspired the legend of El Dorado.

Towards the end of the trip we were able to buy provisions from jungle hamlets (armadillo meat, plantains and rum for example), but in the rainforest we had to carry most of our food supplies. This was a long trek, so we were also counting on our guns to supply some meat. As the Kuna regard almost any animal fair game and must be one of the few tribes in the world that eat big cats, we had to warn our guides about what they could and could not shoot. Teddy argued that jaguar meat was “very tasty” but we were all convinced that it would be a matter of life and death before we were forced to kill one of Latin America’s endangered super-predators. The closest we came to a big cat was the spoor of a puma that had circled our camp one night, perhaps attracted by the scent of paca meat. It was Nuñez de Balboa’s conquistadors who gave the paca its Spanish name, which means ‘painted rabbit’, but the paca is more often described as a giant jungle rat. The meat is tasty but armadillo is better.

During his first expedition Balboa befriended Indian guides who offered support and meat. It was only later that he began to massacre them with swords and vicious war-dogs, and within four years he had been beheaded. The Scottish colonists alienated their Indian neighbours within a short time of settling here and, according to John Prebble’s book The Darien Disaster, their crossing of the mountains was immeasurably harder than either Balboa’s or ours. “They sank to their knees in a millennium of vegetable decay,” Prebble wrote. “They were blinded by leaf-splintered sunlight, and deafened by the raucous protest of hidden birds.” Our trek had been relatively tough but we were neither blinded nor deafened. And only rarely did we sink to our knees.

Fantastic facilities and research sources now make the planning of an expedition easier than ever. Google Earth is the greatest boon for a traveller who is planning a trip into uncharted territory. Far from detracting from the thrill of exploration, increased access to this sort of information can make it easier to get off the beaten track. Many of those empty spaces on the world’s maps – what Joseph Conrad once called “a blank space of delightful mystery” – are now revealed in all their glory, beckoning to the adventurous with their unexplored rivers and unclimbed peaks.

As is so often the case, even the best maps available proved woefully inaccurate, but we also carried a simple handheld Garmin GPS (a Venture HC) and were amazed to find that even under the dense jungle canopy we almost always managed to get a signal. Another backup security measure came in the form of the new state-of-the-art Spot satellite messenger device. I could send a pre-set ‘all ok’ email to a list of recipients back home each evening and, in the event of a real disaster, there was even a ‘panic button’ that would alert rescue services. This cunning gadget also operates as a satellite-tracking system, so that our position was relayed as a blip on a Google Earth page every ten minutes. Family and friends were able to follow our progress through the jungle in something close to real-time, and even before we were able to phone from the coastal town of La Palma they knew that we had made it from coast to coast.

The reassurance that this offered was wonderful, but I knew that once we were on the ground we would soon find that the jungle was still the same jungle that it always had been. With the mud, the insects, the thorns and the sweat, it is one of the most challenging environments in the world. You trudge onward, frequently with mud up to your knees. Several times a day you struggle across rivers with the current swirling around your thighs and your backpack shucked up to keep it high and dry on your shoulders. You can feel your energy drain with the sweat that never stops running and in the tropical heat, scratches and bites soon begin to fester.

It can be tough, and you often wonder why you are doing it. But then, just at the right moment, something beautiful invariably happens to boost sagging morale: a pair of scarlet macaws flap squawking overheard or a giant blue morpho butterfly flitters past – looking like the patch of fallen heaven that the ancient Mayans believed it to be.

While these images are part of the lure of the jungle, the harsh reality is often very different. Spend a little quality time in that Garden of Eden and you soon begin to imagine that every living thing has decided to dedicate its life’s mission to your torment. If it can’t bite you, it will sting you. If it can’t sting you, it will scratch you. If it can’t scratch you, it will, at the very least, do its best to give you a nasty suck.

I had already been warned about the Darien’s giant fulofo poison ants. They resemble bullet ants but deliver a dose of venom that is said to be worse than that of a scorpion. One experienced Central American traveller I know (a big Panamanian weighing in at around about 90 kilograms) spent almost three days vomiting and fainting after being bitten by just two of these vicious insects. I was told that, next to the fer de lance, these were the creatures to be wary of.

One fateful afternoon as we were nearing the end of our trip, I scratched something that was tickling my ear and felt the jab of pain as a fulofo sank its pincers into my finger. I cursed and rubbed the inflamed digit, which began to swell instantly to almost twice its size. Less than fifteen minutes later I was bitten by a second fulofo under my arm. This time – after I had finally convinced my attacker to let go – I just shook my head in stunned disbelief. My best bet now was to get to the next river, make camp and climb into my hammock to try and sleep off the poison before the delirium kicked in.

Half an hour later, as I climbed down to the river to remove the mud of another day’s trekking, I brushed a poisonous plant with my arm. A large patch of blisters instantly broke out over my skin and as I hauled myself from the river after my wash I was stung on the back by a horsefly. In an instant, I finally grasped what the ‘curse of the Darien’ was all about. “Okay, okay!” I shouted at the jungle in general. “I get the message! I’m leaving, okay? Give me a chance, I’m leaving!”

Get there

Get there

Fly from LA to Panama City with Copa Air.

copaair.com

Stay there

Stay there

Panama-based Ancon Expeditions runs tours and expeditions to many of the country’s remote wilderness areas including the unique Cana Field Station, now the only accommodation in the 1.2 million-acre Darien National Park. Built on a mountaintop within sight of the Colombian border, it is one of Latin America’s most outstanding wildlife venues.

anconexpeditions.com