It’s late afternoon and I’m barrelling along the Buntine Highway in the Northern Territory. Cattle country. Here, even the names of dried-up creeks sound like they belong in a Slim Dusty song.

With the sun low in the west, there’s a golden-hour glow illuminating everything: the hardy gums, the tall grasses, the red-earth ant nests. It all feels like the Australiana dream of a landscape painter. I can’t help but smile. As I drive along I’ve got ‘From Little Things Big Things Grow’ playing on the hire-car stereo – it’s a quintessential Australian song that makes me smile all the more.

Gather round people, I’ll tell you a story

An eight-year-long story of power and pride

’Bout British Lord Vestey and Vincent Lingiari

They were opposite men on opposite sides

Apart from the occasional road train, I don’t pass any other vehicles out this way. There’s no phone reception, no billboard advertising, nothing but the long and bumpy highway unravelling before me and flat, dry country all around. Everything is still. The only things I see moving are flocks of screaming cockies above and nervous-looking joeys chancing it by the roadside.

Vestey was fat with money and muscle

Beef was his business, broad was his door

Vincent was lean and spoke very little

He had no bank balance, hard dirt was his floor

My path to begin this trip was itself long and bumpy. Like many Australians, a visit to the outback to spend time in an Indigenous community had always been on my to-do list, but was relegated thanks to the lure of overseas travel. Years ago, when I first heard of the Freedom Day Festival, the idea to make the journey to Kalkarindji, 400 kilometres southwest of Katherine, was born. Still, other things always seemed to get in the way. To be on the road and on the way at last, with that familiar Paul Kelly harmonica refrain calling through the speakers, feels like a bucket-list item is finally being ticked off.

Gurindji were working for nothing but rations

Where once they had gathered the wealth of the land

Daily the oppression got tighter and tighter

Gurindji decided they must make a stand

While many Australians can sing along to the words Paul Kelly and Kev Carmody wrote about Vincent Lingiari and his mob, few know much about their meaning. The place I’m headed, Gurindji country, is where this true story – a story about Aboriginal resistance and the birth of land rights – all begins.

They picked up their swags and started off walking

At Wattie Creek they sat themselves down

Now it don’t sound like much but it sure got tongues talking

Back at the homestead and then in the town

And it’s on Gurindji land, more than half a century on, that Indigenous communities and other Territorians converge each year for the Freedom Day Festival, which commemorates and celebrates the courage of Vincent Lingiari and his people. It’s here in the twin townships of Kalkarindji and Dagaragu that Vincent Lingiari’s family still live, along with the families (and some remaining survivors) of those who joined him in the legendary eight-year struggle – first for wages then for their land.

Vestey man said I’ll double your wages

Seven quid a week you’ll have in your hand

Vincent said uh-huh we’re not talking about wages

We’re sitting right here till we get our land

Despite the political origins of Freedom Day, this festival makes sure it also gives plenty of attention to music, sports and good times. There are indeed some important political and cultural moments throughout, and the history of why this festival exists is never forgotten. Ultimately, though, this is an opportunity for the Gurindji to celebrate and let their hair down.

“Welcome to our country,” says Rob Roy, a Gurindji leader and Traditional Owner, when I arrive in town. “We love having you mob from down south come here to visit. Settle in, relax and enjoy yourself.”

As far as bush festivals go, Freedom Day is about as down to earth and back to basics as it gets. Out-of-towners generally set up a campsite somewhere around the edges of Kalkarindji. The weekend schedule is loose and likely to change. All the events – from the music to the footy – are within walking distance of each other. It’s hot, dusty, slow-paced and unpretentious. Even headline acts like Dan Sultan and visiting politicians like Richard Di Natale sleep in tents and line up for the showers just like everyone else.

On Friday, the first day of the three-day event, people gather for the Freedom Day March. With an assorted mix of locals, politicians, union leaders, anti-fracking campaigners and visiting festivalgoers, we first listen to the Welcome to Country and some speeches, then we begin to march as one, honouring those who walked off the job back in the day, with hundreds of bright flags colouring the way.

I walk with Charlie Ward, Gurindji historian and author of the book, A Handful of Sand. The title references the iconic image of Gough Whitlam symbolically giving back the earth to Vincent Lingiari by pouring it into his hand.

“Kicking off the festival with the march means a lot to the Gurindji mob,” says Ward. “It began with the strike leaders wanting to remind the next generation of the sacrifices they’d made in their long struggle for freedom, and the journey from Vestey’s Wave Hill Station that began it all.” And so the festival begins.

Over the next three days, I attend talks at the art centre and buy a piece of local art. I watch barefoot basketball matches take place on the town’s new courts. I enjoy plenty of games of footy, with teams from all over the Territory battling it out to take out the top prize.

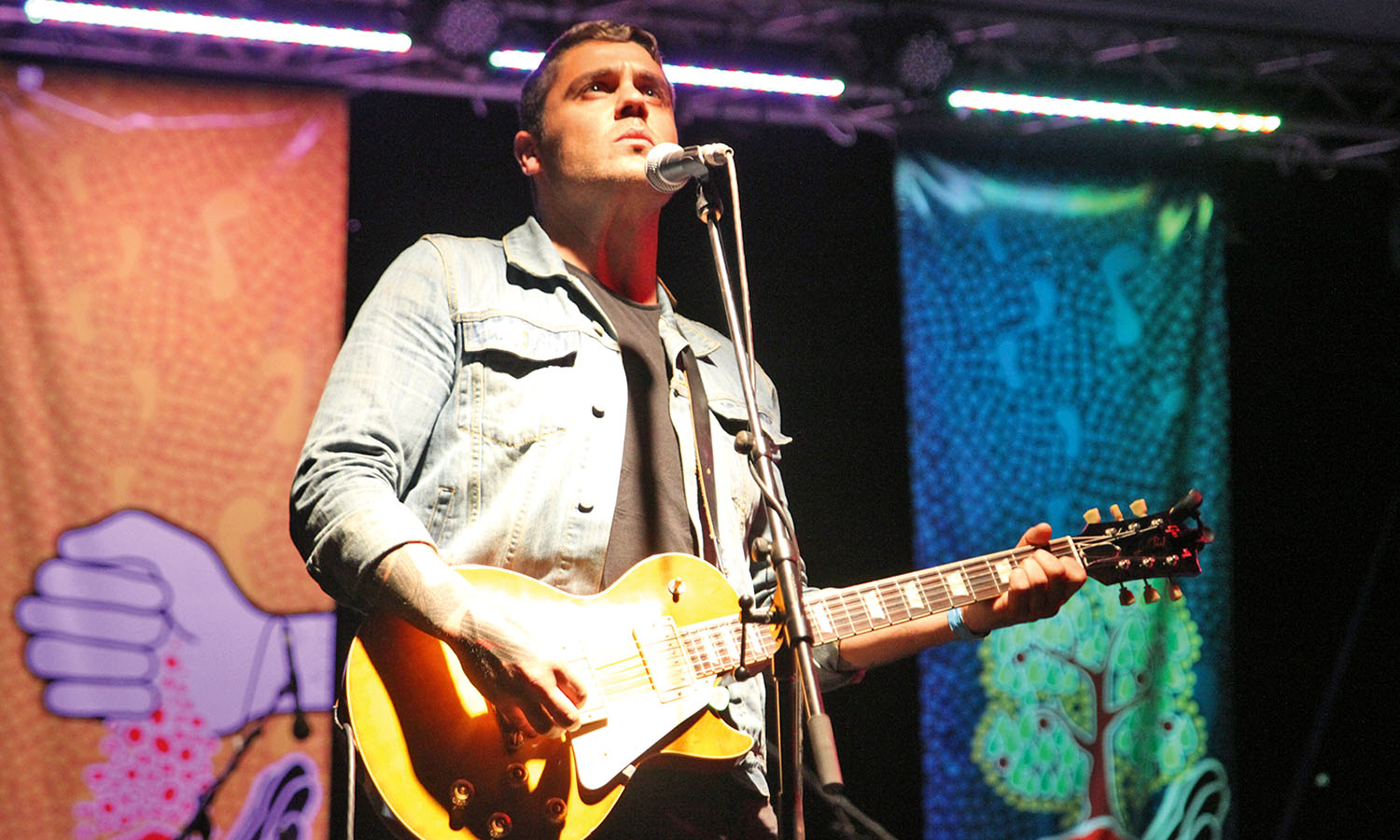

And I meet and chat with local Gurindji people, who seem proud to be showcasing their country to visitors who’ve come in from out of town. It’s the music, however, that really grabs my attention. The eclectic selection of performers – from folk singers to Johnny Cash impersonators, hip-hop stars to bush bands like Sunrise Band, Rayella, Mambali, Robbie Janama Mills and Lajumanu Teenage Band, who are the crowd favourites – is a real treat. It’s the bush bands that really get the Gurindji crowd kicking up dust on the dance floor. Each band offers an honest brand of music that fuses big, crunchy guitar rock with reggae then adds in an Indigenous twist, often with lyrics sung in their local languages and the introduction of digeridoos and clapsticks. While it’s a delight to see some big-name acts out here in this place, I have to agree with the locals – watching these homegrown bands, with the full moon overhead, is a highlight.

“We reckon this is possibly the best bush-band line-up on offer anywhere in the Territory,” says Phil Smith, a Gurindji Aboriginal Corporation employee and festival director. “And when we throw the likes of Dan Sultan, Remi and Baker Boy into the mix, this becomes a festival well worth travelling to from anywhere across the country.”

I couldn’t agree more. The Freedom Day Festival is everything I’d hoped for. There’s a sense of camaraderie among those who’ve travelled so far to attend, and a sense of gratefulness from the Gurindji for us making the journey to help honour their story and visit their land. As the epic fireworks show cascades across the sky, and the young ones who’ve never seen such a thing look up with mouths wide open, I feel privileged to be a part of all of this.

Talking with some of the Gurindji people on my final day, I learn the Vincent Lingiari story, as told in the song, is much more than eight years long. It’s a story that continues to this day. Lingiari’s vision for self-determination and self-sufficiency is one that endures. The success of this festival, I’m told, as it gets bigger and better each year, is undoubtedly another step towards moving things in this direction.

As I pack up and prepare to leave this place I can’t help but think that if more visitors make the time to come to Gurindji country each year, they’ll be helping make this vision a reality in their own small way.

From little things big things grow.

From little things big things grow.

Get there

Get there

The closest airport to Kalkarindji is Darwin, almost 10 hours’ drive north. Virgin Australia flies there direct from most capital cities and with connections from other centres. Hertz offers 4WD rentals at Darwin Airport.

virginaustralia.com

hertz.com.au

Stay there

Stay there

Several nearby campgrounds are provided where visitors can set up their own self-sufficient bush camps. There are bathroom facilities but no campsite electricity.

Get inforMed

Get inforMed

The Freedom Day Festival is held in August each year. Entry is free, although donations to the website to help run the festival are appreciated.

freedomday.com.au