A 14-year-old-boy pointed his gun at me, as I crouched nervously on my haunches.

We were squatting with about 20 others in a circle while the leader, a smartly dressed man with a beard, conducted things from the centre of the ring. There were about 200 other men in the room.

A few had warned us not to go to Iran.

I thought of this as we waited to see how the situation would unfold. I looked at Henri, who was doing well to conceal his terror. We were petrified at being called into the middle, as there was just no way we could possibly match this dancing, all sinuous, affectionate and enthusiastic – like some troupe of Middle Eastern M.C Hammers.

The circle was filled with guests at the wedding we’d been invited to, and the smartly dressed man was the groom, a cousin of Hamid, the friend we’d made in Isfahan. The 14-year-old boy’s gun was his fingers twisted into the shape of a gun, which he would occasionally point at me in fits of laughter until I returned fire in a game that lasted all night, although I’m still not sure of its meaning. Right now the groom was bringing individuals up one by one to dance with him in front of everyone.

It is worth mentioning that we had only met Hamid two days earlier, in cliche fashion: over a cup of chai in his carpet shop. His willingness to acquire extra invitations for two white westerners he’d only just met, with no commercial gain on his end, was our first introduction to the famed level of Iranian hospitality.

Isfahan is a busy city with a population of a couple million. Stunning Persian architecture line the streets in the city centre, while endless sand dunes flank the outskirts, where camping, sandboarding and trekking are all popular.

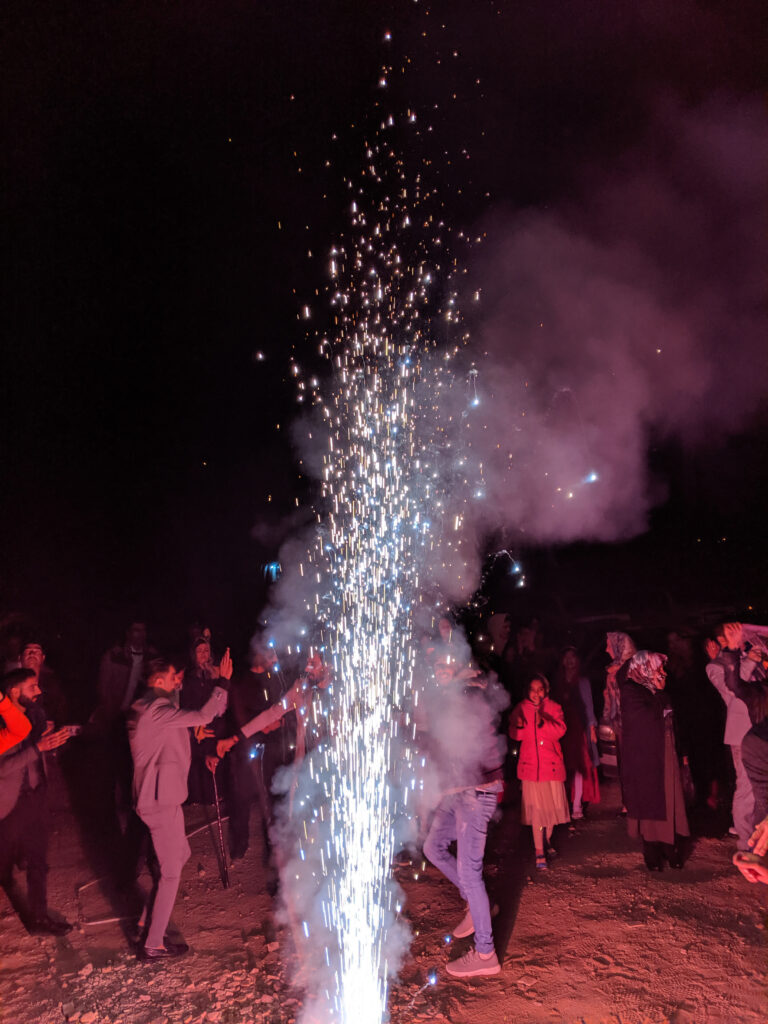

Based on a family’s level of conservatism, weddings here are generally (after a brief but extravagant ceremony) split into two parties based on gender. We’d watched at the start of the night as the bride and groom walked down a makeshift aisle to fireworks and flares, before dramatically releasing two white doves into the night sky. Shortly after we said goodbye to the girls, who disappeared into a separate hall to us.

Women and men split into two seperate rooms after the walk down the aisle.

Women and men split into two seperate rooms after the walk down the aisle.

What followed was six hours of delectable food, wild dancing and selfies, as we came to terms with our celebrity status at the event. Happy and gregarious Iranian men came from everywhere to introduce themselves, hugging and kissing and welcoming us to Isfahan. It seemed everyone wanted to dance with us, to know what we did for a living and to tell us about their relative in Sydney.

After our turn dancing in the middle we were beckoned over to the table of Imam, a tall and mischievous looking character who was probably the least conservative of Hamid’s endless line of cousins. With a dangerous look in his eye he reached into his jacket and pulled out no less than 20 small cucumbers, placing them on the table. This seemed extraordinarily random on face-value, but our modus operandi by this stage was to go with it.

The cucumbers turned out to be chasers for arak, a lethal home-brew spirit which I found almost undrinkable, but ended up drinking quite a lot of. While alcohol is illegal nationwide, a blind eye is turned to occasions behind closed doors like this.

When the DJ’s eclectic mix of Arab-disco and Pitbull (he truly is Mr. Worldwide) concluded we filed out of the building, waving goodbye to the happy couple as they got into their car and drove off. End of the night, it would seem.

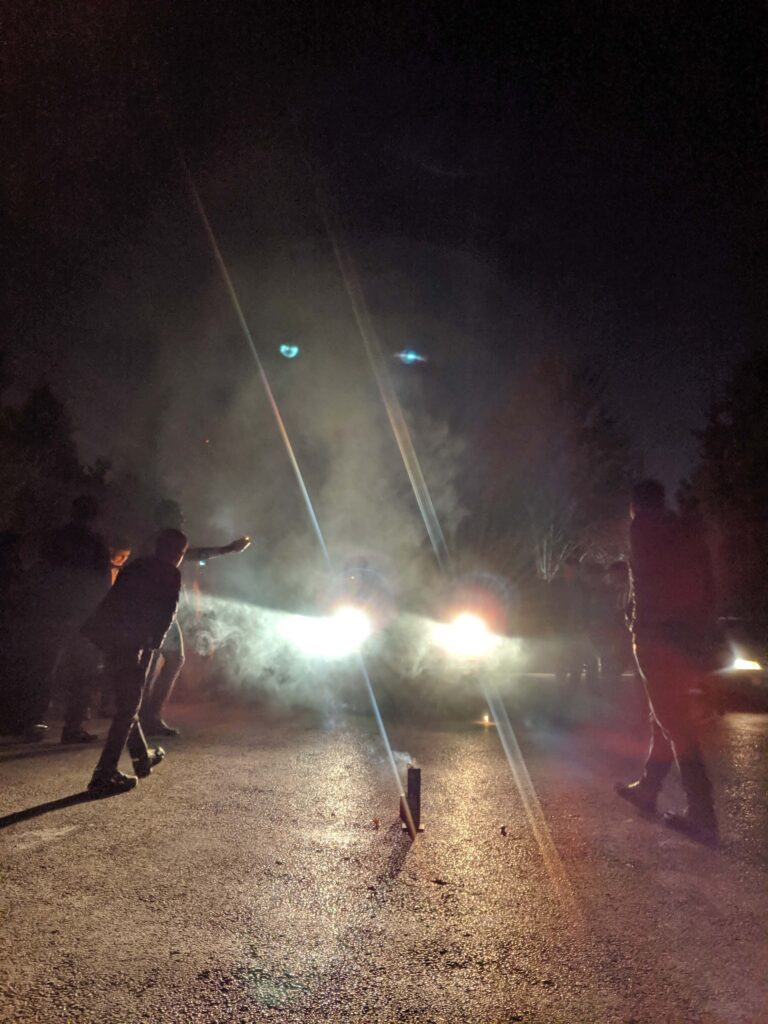

This however, proved to be a false conclusion. With Hamid at the wheel, and eight grown men packed into a tiny Fiat, we sped off after the newlyweds in a convoy of around 30 cars, swerving and maneuvering at 100kph and waving white towels out of the window on a highway. Lanes became obsolete in a game where the aim seemed to be to get as close to the bride and groom’s chariot as possible without touching it. Every 10 minutes or so we would all pull over to the side of the road, or down a sandy back alley, for some more dancing and fireworks before piling back into Hamid’s car for another game of cat and mouse.

The race ended at the bride’s mother’s house, where (after more fireworks and dancing) an unlucky sheep was slaughtered in the name of love, a sacrifice the two guests at the wedding certainly didn’t see coming.

In the middle of nowhere, and without any idea of how to get home, we turned around to find our taxi driver from the start of the night ready to take us home – having waited for six hours and kept up with us in the speedy procession. We might have been surprised, but by now we were getting used to that feeling.