Admittedly, the Vision is armed with side-thrusters, which make positioning the boat remarkably easy, but while getting into locks is one thing limboing under eighteenth-century bridges in the river version of the QE2 is another matter altogether.

“Your glass of wine, that will be OK,” Dominic explained, before letting us loose. “But the bottle, well, you might need to move that off the table when you pass under the lowest of the bridges.”

We assumed he was joking, but no, they really are that tight – as my wife discovered when she escaped a beheading by mere millimetres while unwittingly climbing the stairs to the top deck just as we passed under a particularly low bridge. I shouted a warning just in time, mercifully (she was bringing me a cold Kronenbourg after all).

During our week-long expedition through the Yonne Valley, we pass the glorious green embrace of the Morvan, a beautiful expanse of wild woods, where tracks and trails spider off in various directions, most of them eventually leading to hilltop hamlets. Cycling along one of these trails one morning I almost crash headlong into a wild deer.

There’s a slight 28 Days Later feel to some of the medieval villages we discover while exploring. Mailly-le-Château, for instance, is a quiet and eerie eyrie, where the streets are almost surreally tidy, the gardens well tended and everything is in its right place, yet the streets are spookily empty. Zombie apocalypse or not, there’s almost always a cracking boulangerie in these places, but who they sell their magnificent bread and cakes to when we don’t happen to chance by, I’ve no idea.

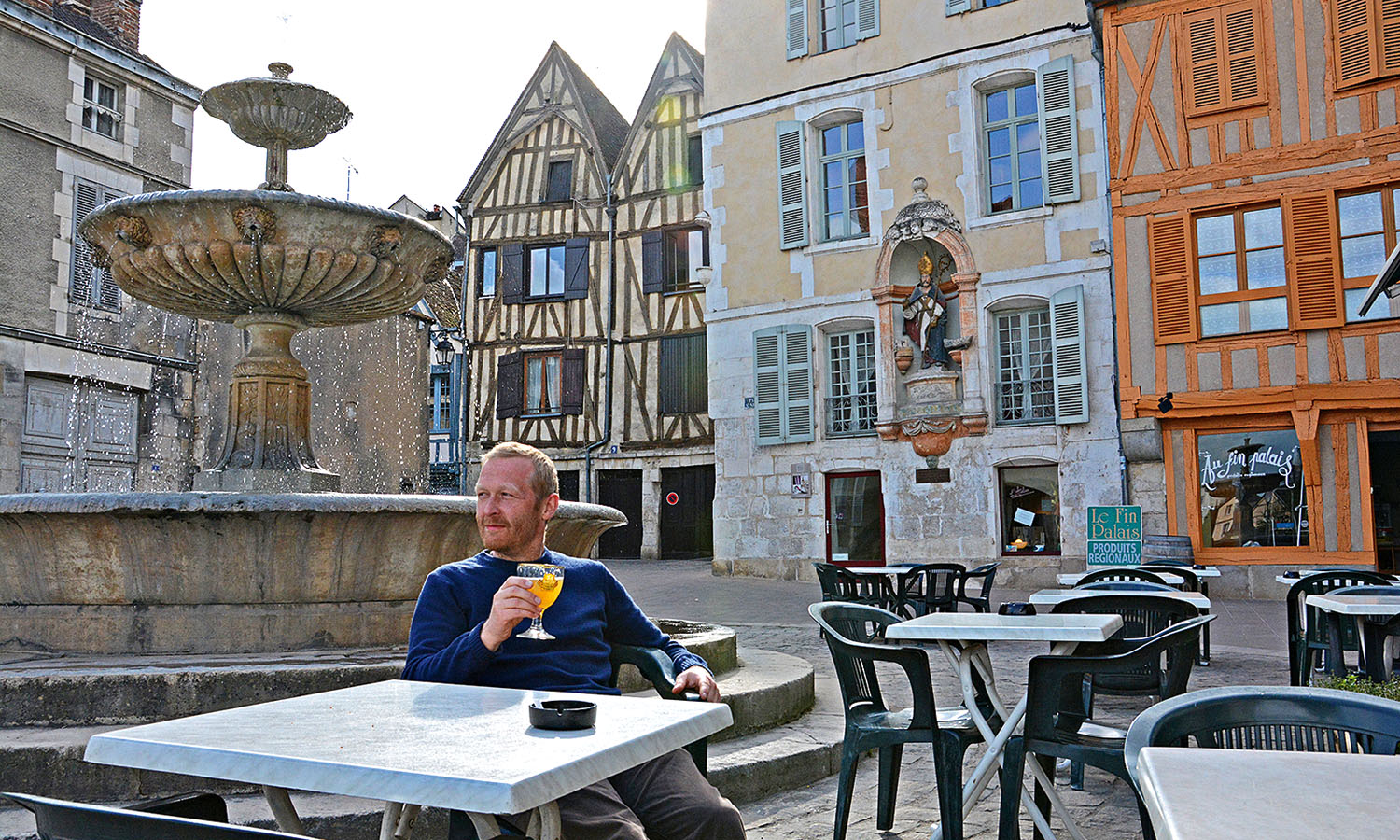

Far more vibrant are the two bigger towns we pass through, Auxerre and Clamecy. The spire of Saint-Étienne Cathedral, visible from several river bends back, announced our imminent arrival in Auxerre on the second day. The lively town revolves around this edifice, parts of which date back to the eleventh century. We moor right next to a little plaza that leads straight to its enormous doors – more central accommodation it would be impossible to find.

The town is busy with bustling restaurants, bars, cafes, shops and tabacs, but we don’t hear a single non-French voice while exploring the streets. Besides the Kiwis, we appear to be the only blow-ins. It’s hard to discern whether this is because it’s early in the season or if this part of France is just well off the tourist map.

While the villages of the Bourgogne are quiet, the locks along the canal are social hubs for boaters. Even now, during the quiet kick-off to the season, it’s common for lock keepers to squeeze two or three boats into each lock. As you stand on deck with a rope in your hand, ready to brace against the buffeting onrush of water, conversations flow between craft.

It transpires that many of our canal-cruising comrades own their boats and live the life aquatic almost full time. A few are French, but others have transported their barges and river cruisers from the UK or elsewhere. Some of these waterborne wanderers are on epic voyages, linking together canals and rivers to traverse large swathes of Europe.

Intrigued, I do a bit of research (our flashpacking boat has wi-fi) and discover you can take a canal boat a bloody long way if you put your mind to it. Some people have attempted trips from Paris to Moscow, even continuing up to Arkhangelsk on the shores of the White Sea in Russia’s north.

There’s a whole nomadic canal-boat counterculture here I never knew existed. It’s an idea to file in my to-do-when-I-retire-loaded list, but for now I’ll be happy to make it to Tannay in one piece. Tomorrow we’ve got a shindig planned in Clamecy, our last stop before relinquishing the Vision. But first we have to face the hungry hordes waiting back on the boat.

“I think there is some brioche left over from yesterday in one of the cupboards,” says George, grasping at straws as we swoop down the hill and away from the vino cave.

Perfect. The people have no bread? Well, let them eat cake. That line worked out a treat for the last person who tried it around here. Marie Antoinette got the chop for her bourgeois indifference to poverty when this canal was just nine years old.

Ah well, if we’re going to get it in the neck, at least we’ve been anesthetised with the world’s best Crémant.

Europeans love to bag Belgium, insinuating that the country offers little but mayonnaise on fries. And while this is a brilliant food combo, the country has much more going for it than its ‘boring’ reputation suggests.

On the surface, Belgium is a country divided, both regionally and linguistically. Years of tense debate and power struggles between the Flemish and French communities have left the nation with a confused identity. But look a little closer and you’ll realise each city and village tells its own story with a unique narrative and voice.

The port city of Antwerp is the cultural hub of Belgium and home to the prestigious fashion museum MoMu. The city is also famous for its diamond trade and literary community. Bruges is a fairytale wonderland on water, and Brussels, despite an austere façade, has a raging cafe and bar scene. Dive in and discover Belgium’s depths.

(

(