“Were you scared back there?” they joke as we throw down beers and lather our deep-fried lunch in a Chilean salsa called pebre.

“Only a little bit,” I lie. “Next time just strap me to the horse.”

If Selkirk trekked over these crumbling mounds on a regular basis and lived to tell the tale, I tip my hat to the man. But I tend to agree with most modern researchers who believe he likely toiled away his days of solitude in the very place the island’s 800 modern-day residents do, along Cumberland Bay. There’s a sliver of flat land, calmer seas and a lookout with views to the southeast where rescue ships rounding Cape Horn were most likely to appear.

The next morning I set out to explore the corner of this boomerang-shaped island neighbouring San Juan Bautista – the area that Selkirk may have roamed. The surroundings can’t be much different than 300 years ago, as this UNESCO Biosphere Reserve is, to this day, 13 times richer in bird life than the Galapagos, with 61 times the plant diversity, including the peculiar pangue, a species that evolved slowly in isolation.

Stepping into a forest of pangue just beyond Plazoleta del Yunque, one hour above town, is like entering Alice’s wonderland. A path from the picnic and camping area disappears into a curtain of leaves as large as a human body, then loops into a dense jungle of endemic flora. Home to both the firecrown hummingbird and short-eared owl, it’s a landscape where frazzled ferns that wouldn’t be out of place in New Zealand’s Fiordland elbow for space next to pencil-thin palms reminiscent of Hawaii.

This serene spot was once the refuge of the German Robinson Crusoe, a man by the name of Hugo Weber Fachinger, who survived the sinking of SMS Dresden just offshore during World War I and eventually settled on the island in isolation from his captors. Fachinger chronicled his adventures for several European magazines of the time (much as Selkirk did upon his return to Scotland) but was forced to leave in 1943 when he was wrongly accused of being a Nazi spy.

The path from Fachinger’s hideout back to San Juan Bautista traverses a different microclimate altogether, where wind-deformed trees cower over a herbaceous steppe, their gnarled branches swept over like a lopsided ponytail. Closer to town the surroundings change once again into a forest of newly planted pine and eucalyptus, resources absent in Selkirk’s day that are now used for construction and heating.

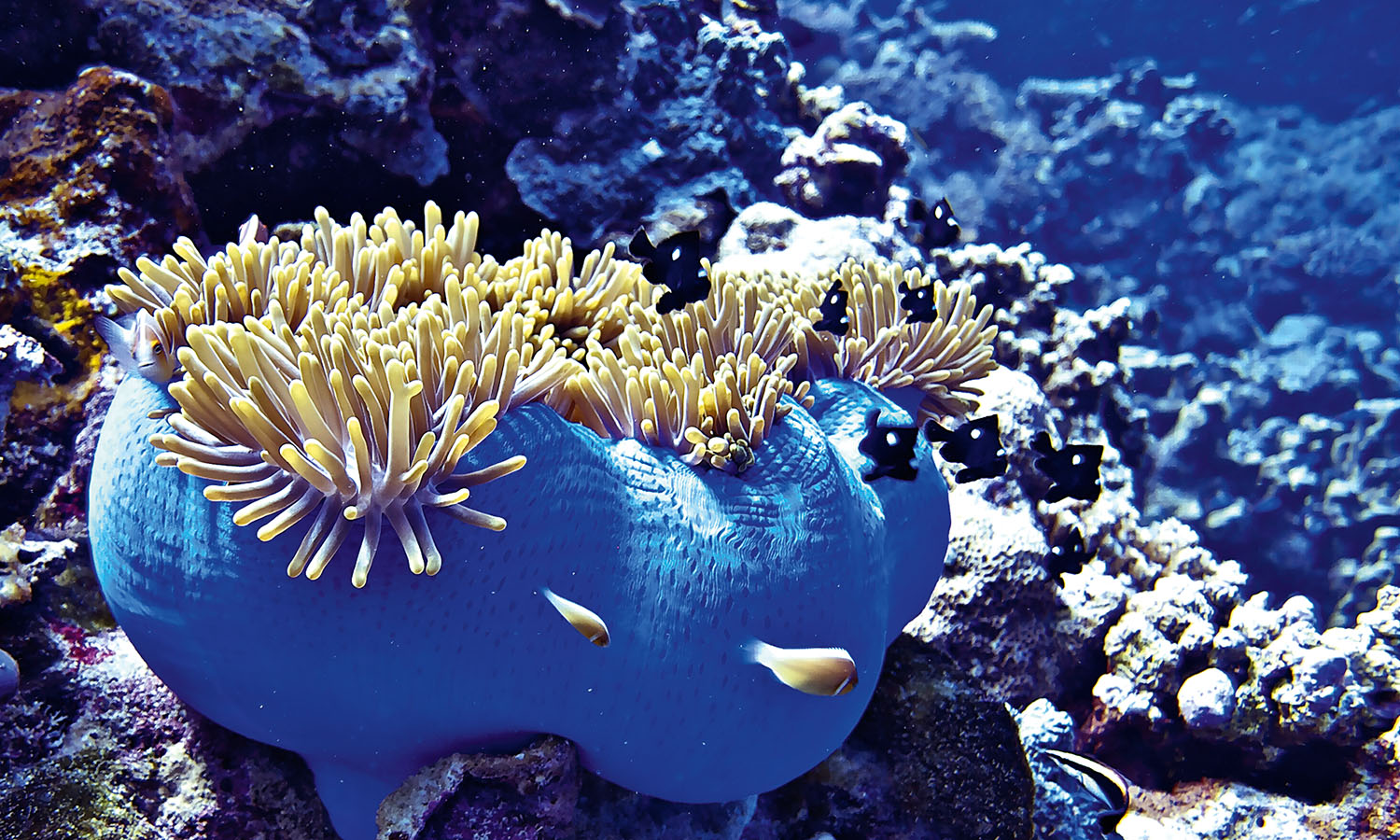

Robinson Crusoe Island is hardly the cut-off-from-the-world backwater it once was. The wood-carved town of San Juan Bautista was virtually rebuilt from the ground up after a devastating 2010 tsunami, and now boasts satellite TVs, wi-fi, sprawling plazas and open-air restaurants with the kind of high-quality, low-fuss seafood found in salty fishing towns. Rock lobster, golden crab, octopus, sea bass – you name it, this island has it, thanks to its location at the confluence of the cool Humboldt Current and warm Pacific Countercurrent.

A more appropriate question might have been: “Are you afraid of perilous rock slides and slipping into an abyss?” To which I would have replied: “Yes. As a matter of fact, I am.”

Chefs will cook up the catch of the day in one of three ways: chopped into a ceviche, wrapped up in an empanada or grilled à la plancha. Of the dozen or so restaurants scattered across town, the breka ceviche at Brisas Del Mar is easily the best deal at 2000 pesos (AU$4), while the steamed lobster at Crusoe Island Lodge is top of the line – with a price to match.

Selkirk would surely roll in his grave if he knew how much a Juan Fernandez rock lobster retails for in Chile, not to mention his native Scotland, where the shellfish is considered a rare delicacy. These lobsters were simply a means of survival for the castaway – a daily dose

of energy for a man locked up in an island prison. Now, they’re red gold.

Long gone are the days when you could pluck lobsters off the pebbled beaches of Cumberland Bay, so I pull on an extra layer of blubber (my wetsuit) and snorkel offshore with Francisco to see if I can find dinner. What I find instead are the island’s notoriously playful and childishly inquisitive fur seals.

Three zip over to check me out the moment I plop into the bay. They have a stealth I didn’t think possible of a clumsy sea mammal

and are absolutely acrobatic under water, darting headfirst through the sea, their whiskers bending into moustaches.

The welcome party scurries in and out of view for about five minutes, performs a few feats of agility, then retreats to a rocky perch to do what seals do best: suntan, bark and waddle around, all in the company of a few hundred friends.

It was the ancestors of these very seals – large in number and menacing in appearance – that eventually drove Selkirk away from the coast, according to historical accounts. He’s thought to have moved further up into the hills, where he built a hut and domesticated goats, introduced by earlier sailors, for food, clothing and companionship.

There are two ways to get from San Juan Bautista to the airport on the far side of the island. One is by boat. The other is by foot, passing Selkirk’s old hut, his namesake lookout, and the side of the island that bears a striking resemblance to the castaway’s homeland, yet likely remained an inaccessible mystery.

I choose the six-hour walk for my last day in the Juan Fernandez. Halfway up the rugged volcanic range that separates San Juan Bautista from the far side of the island, I come across a trail leading to the remains of what Japanese explorer Daisuke Takahashi claims is Selkirk’s main hut. The pile of rocks isn’t much to look at now, but excavations sponsored by the National Geographic Society a decade ago revealed a few tangible links to the Scottish privateer, including a blue tip from a copper navigational device commonly used by sailors of Selkirk’s time.

(

(