Notorious for crowded trains and chaotic roads, India may not be the first place you’d think to explore by camel. But the 200,000-square-kilometre Thar Desert provides ample opportunity to do just that.

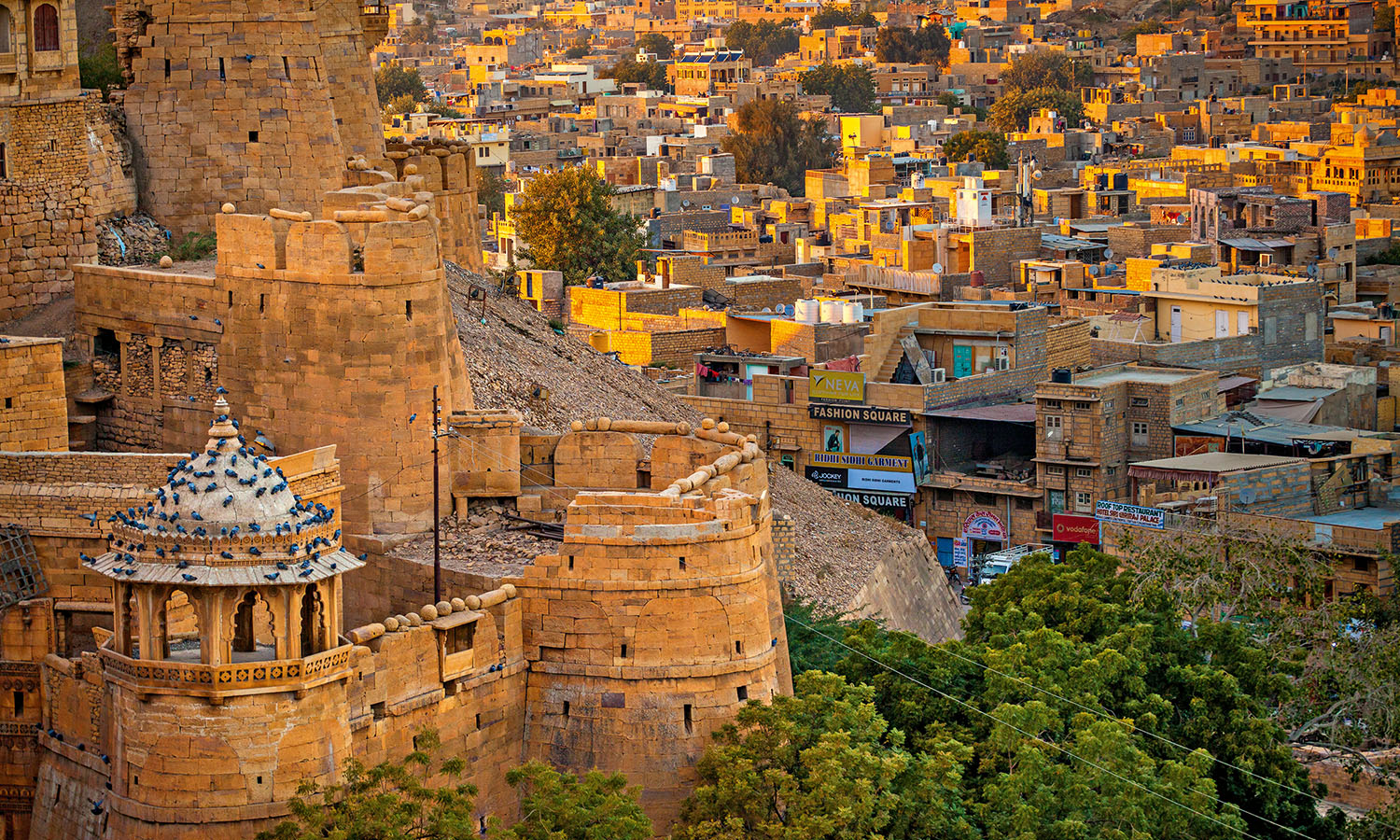

I’d arrived in Jaisalmer with three friends to embark on an epic five-day camel safari through the Great Indian Desert. Home to 80,000 inhabitants and located 575 kilometres west of Jaipur, the state capital of Rajasthan, Jaisalmer is a desert city protected by an impressive World Heritage-listed fort built on a sandstone ridge that dominates the surrounding desert. Looking very much like a sandcastle rising majestically above the flat sandy expanse, this desert citadel, guarding an impressive palace complex containing several ornate rooms, buildings and Jain temples, harks back to the days of the Rajput warrior clans.

Inside the fort’s sandstone walls, there’s a labyrinth of lively small streets populated by smiling merchants peddling spices, wooden idols, books and all sorts of exotic handicrafts. Flanking these lanes are magnificent havelis (private mansions) decorated with intricate latticework and floral designs, carved from wood and stone and dating back at least 500 years.

Walking through the narrow winding lanes up to the palace complex, I stumble upon handprints etched into the sandstone. They tell the story of the fort’s rather macabre past as the site of countless jauhar (mass suicides) throughout the Islamic invasion of India in the Middle Ages. The women and children self-immolated within these walls in accordance with this ancient Rajput tradition in a bid to avoid capture, enslavement and dishonour.

Entering a small chai shop, I’m greeted by a cheerful shopkeeper who gives me a brief lesson on the strategic importance of the city in centuries past. As a stopping point for camel caravans along a traditional overland trade route that linked India with Europe, the Middle East and Central Asia, Jaisalmer grew in wealth and was fiercely protected by clans of Rajput warriors who wielded gilt-edged swords and claimed descent from Hindu deities.

We poke fun at each other’s turbans before returning to our own little worlds as we watch the burning red sun slowly sink below the horizon. There really isn’t too much to say out in the desert.

Upon waking the next day, I have the faintest recollection of a dream. I remember walking through sand dunes and stumbling upon an old man charming his cobra. He was wearing a red turban and, with his wrinkled, sun-baked skin, looked about a hundred years old. As he played his flute, the charcoal-coloured snake gently swayed from side to side. I tried to speak to the man, but he was in a trance. I edged closer, trying to get him to notice me. Suddenly the cobra turned around and latched onto my arm – and that’s where the dream ended. Lying in bed in the early morning light, I see my friends already stuffing their backpacks. I can’t help but feel a little anxious.

We’ve been told temperatures will fall below zero come nightfall out in the land of shifting sand dunes, broken rocks and scrub. We were also warned that there would be no chance of a shower, no electricity and minimal food and water over the course of the five days.

This matters very little – at least to me. What a way to spend Christmas, I tell myself over and over again as we leave our guesthouse early in the back of an old Mahindra jeep, driven by a burly Brahmin who, with a big white beard, is reminiscent of Mr Claus. Just like those wise men 2000 years ago who were led by a luminous, twinkling star in the deserts of the Middle East, we are being led by the promise of adventure, hardship and a once in a lifetime experience. It’s been a long time since I was this excited about the festive season.

Cruising out of town, we pass crumbling buildings, groups of locals and the occasional cow. Some 40 kilometres shy of the India–Pakistan border the jeep begins to slow then veers off to the side of the road onto loose gravel. “There are your camels,” says the driver, pointing to a colourful caravan on the horizon.

We disembark, collect our bags and stare into the distance, waiting for our rides to arrive. The Indian sun blazes above us in the clear blue sky, yet it’s quite cold – about 10ºC or so.

Waiting for our adventure to begin, I take a moment to breathe and absorb my alien surrounds. The epic panorama of this arid, dusty landscape envelops us. There is yellow and rust-red sand, rocks large and small, and khaki-coloured foliage strewn across the land as far as the eye can see. At the horizon these colours merge with soft, light blues, gradually morphing into deeper hues the higher into the sky you stare.

In the distance windmills dot the expanse, and there’s a lonely settlement of cream-coloured, single-storey buildings. People carrying on a traditional desert life populate these local villages.

(

(