“Good to meet you Happy Coconut, I don’t suppose you happen to know Chicken Pizza do you?” I ask.

“Sure, of course,” says a smiling Happy Coconut. “Chicken Pizza is my friend.”

“Can you tell him Cheese on Toast from Monkey Bay says hi,” I say.

“No I can’t, Chicken Pizza is in Finland,” he tells me.

“Yeah, he’s visiting his girlfriend,” Boobs confirms.

Welcome to Malawi, home to some of the friendliest people on the planet, with some of the world’s weirdest names.

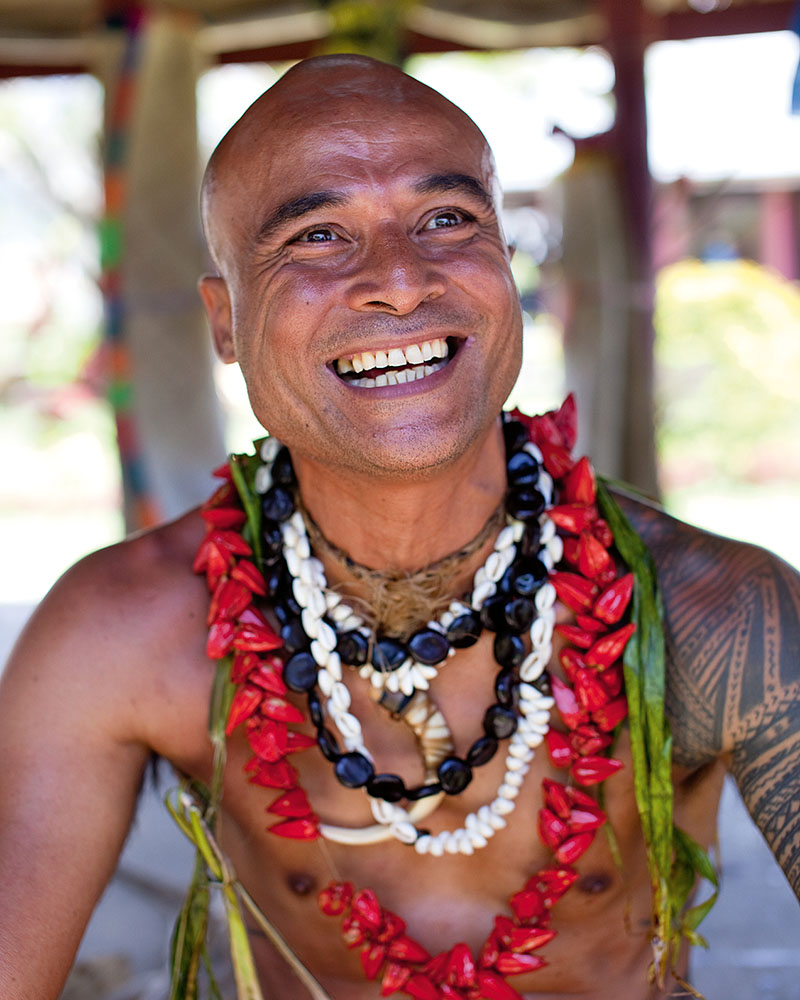

I meet Happy Coconut, an entrepreneurial part-time artist who sources carvings, jewellery and artworks for travellers, in Nkhata Bay. He tells me over a few beers that he changed his name to something catchier, so travellers would remember him and return to buy his wares. It’s a good fit – he is always smiling.

I ask him about the other names around town.

“There’s Soil, Gift and Happiness – they’re nice. But then we have a few Troubles. They always end up bad,” he laughs.

Malawi also has a bunch of clichéd names to describe the country itself. It’s known as ‘the warm heart of Africa’, which describes the spirit of the people. I’ve also heard it referred to as ‘Africa for beginners’ or ‘Africa light’, as if having a real, yet safe, African experience is a bad thing.

Yet of all the titles, ‘The Lake of Stars’ is the one that defined my experience as I travelled from Monkey Bay in the south of Lake Malawi to Nkhata Bay, where I am volunteering on a community project called the Butterfly Space.

This name was given to the lake in the 1800s by David Livingstone, when he saw lights from the lanterns of fishermen and thought they were stars in the sky. It’s also the name of the area’s annual four-day international music festival. But, to me, it’s a name that best sums up the people around here: ‘the stars’. And I don’t mean Madonna.

Her association with Malawi is well documented after she adopted two local children under questionable circumstances. However, while I intend helping out at a nursery school here, unlike Madonna I plan to leave the kids in Malawi when I depart.

Lake Malawi is the aquatic highway and main vein of the country. It’s bordered by Tanzania and Mozambique, and, at more than 500 kilometres long, is the eighth largest lake in the world. It’s the source of water, food and life for the people of Malawi, and is a big attraction for travellers and biologists. With tropical-postcard waters, hundreds of fish species (many exclusive to Malawi), and white sandy beaches with smatterings of coconut trees, it looks more like the Caribbean than a freshwater lake.

My journey begins at Monkey Bay, where I wait to board the Ilala ferry, a 1950s steamliner that travels from the south to the north of the lake, stopping at ports and islands in Malawi and Mozambique.

The Ilala has been out of service for a week, but according to Cheese on Toast (the barman) and Owen, the chief safety officer for the Ilala, who I meet at the bar, it is set to leave the following day.

The day comes and goes, but the Ilala doesn’t. Owen assures me it will be ready to leave at midnight the next night. It isn’t. He phones several times during the night with updates to help me out. The final phone call comes at 4am, after he’s worked all night. “Come down to the wharf, we’re ready to go.”

I grumble as I walk for half an hour in the rain to board. There’s no one to drive me because the car at the hostel has run out of petrol and can’t be filled up due to supply issues that had filtered down from the political crisis in Zimbabwe.

I am embarrassed by my petty complaints as soon as I see scores of locals lying on cardboard boxes on the concrete floor, waiting patiently – no complaints – at the ferry terminal. They’ve been here for more than a week.

It’s even more embarrassing when I board the ferry before everyone else does, just because I can afford the US$115 ticket that entitles me to a comfortable bed for the three-day journey. It’s an old-school basic cabin on the second floor, above the locals clambering for a space to sit among the varied cargo of boxes, bags of cement, smoked fish and bleating goats.

On the top floor is the overstated first-class area, where the simple bar is located and where many travellers spend their time sleeping on mattresses on the deck.

The days pass way too quickly. It’s like being on a no-frills cruise ship, relaxing with books and beers and conversation. The Ilala chugs slowly along, making designated stops to pick up and offload cargo and passengers. The sun shines life into the colours of the lake, the jungle and mountains surrounding it. But it is most impressive when it sets and pinks the African sky.

Although the lake looks more like an ocean, Lloyd the engineer tells me it’s definitely not. It also doesn’t have mermaids, and neither does the real ocean. He knows this because he was fortunate enough to see the ocean once, while studying in Japan on a scholarship. He waited for the mermaids to surface, just as he’d imagined from the stories his aunty told him when he was a child. Very few people in Malawi ever get to see the ocean, so he was most disappointed to return home and have to tell his family his aunty had been lying.

The ferry finally pulls into Nkhata Bay at around 2am, but the supplies take hours to unload so Kahlua the barman lets me sleep and wakes me in time to get off at dawn.

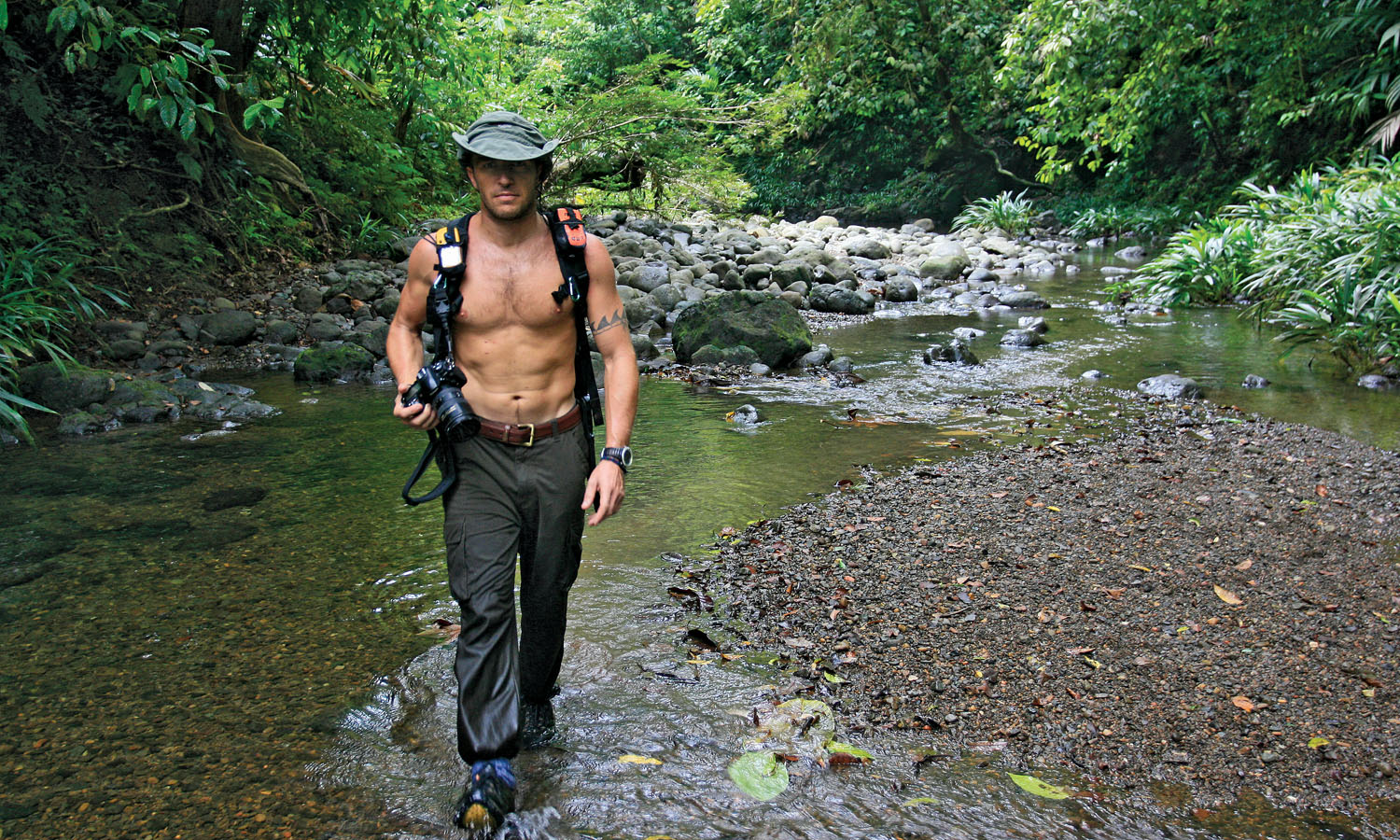

I walk through the markets and village, and around the bay to a rustic timber cabin situated over the water at the Butterfly Space. This is a unique place where you can live for next to nothing, swim and snorkel in tropical waters, eat fresh fish, explore nearby islands, meet great people and also make a positive contribution.

Alice Leaper (AJ) and Josie Redmonds started the Butterfly Space in 2007 to help the people of Lake Malawi.

“It’s about creating opportunities, that’s the philosophy,” says Josie, who had spent previous years volunteering throughout Africa. “We want people to be able to change their own situation the way they want to, rather than it being forced on them from the outside.”

Volunteers here don’t pay to help, they just chip in for their food and board. In fact, the Butterfly Space will not be associated with any other organisations or websites charging volunteers fees. This is because they feel strongly that any money raised should go straight into the projects an organisation runs, rather than supporting the business of volunteering, which is now the case with many other volunteer groups in Africa.

The Butterfly Space provides a nursery school, youth group, soccer and netball team with coach, music groups, special needs groups for adults and gardening projects for schools. There’s a room full of take-home educational handouts, and computers for the kids to use for free. There’s also an HIV lunch program that involves cooking and creating healthy meals to aid awareness of dietary requirements.

(

(