Travel often takes us back in time and Norden Camp is no exception. Built by Tibetan nomads, the retreat has been designed to share the heritage of the land and people with its guests, fusing comfort and eco-sustainability with culture. Eight log cabins constructed from pine found in the woodlands and four hand–spun yak-hair tents dot the countryside, each featuring timber floors, luxe bedding and local antiquities.

The land is untouched by mainstream development so the seasonal produce – herbs, yak milk and black pig – is completely organic and used to create unique delicacies. Immerse yourself in the quiet surrounds with yoga, go horseback riding across the valley, or visit the famous monastic village of Labrang. Out here, it’s all about disconnecting from modern society – after all, you’ve got nothing but time.

region: Asia

Cycle Thailand’s tribal lands

Escape the chaos of Bangkok and go bush in Chiang Mai’s hinterland. Admire Lanna-style temples as you cycle through rainforests and longan plantations, sampling fruit straight from the trees. Take your time pedalling to Wiang Takan, a ruined city that dates back to the twelfth century, and get your blood pumping on an uphill hike before arriving at your first of two homestays in Karen tribal lands.

At dawn, set out for Mae Wang National Park, where you’ll traverse well-trodden paths and overgrown trails, inhaling the fresh scent of ginger and orchids, and meeting locals along the way. On your final day, soak up nature while cruising down the Wang River on a bamboo raft.

Glamping Retreat

Love the rustic adventures Cambodia has to offer but can’t go without your creature comforts? This exclusive two-day day, one-night glamping trip has you covered. Start your morning with a Jeep expedition through the stirring rural landscape and nearby villages, before arriving at the calming moss covered stone temple of Prei Monti and the tangled vine bound temple of Beng Mealea.

Unwind with a picnic lunch at Poeung Komnou, an ancient sight of intricate Hindu carvings set among green surrounds, then head to the campsite where you’ll be greeted and treated with a chilled cocktail to kick start your evening. After soaking in the comforts of your own private and lavish tent, experience a gastronomic delight with dinner cooked by the Heritage Restaurant team from the Heritage Suites Hotel. This outside dinning is the perfect mix of nature and glamour with hundreds of tea-light candles flickering over your skin that sets the scene for a relaxing evening. Next morning tuck into a huge breakfast spread before stepping back in time with a ride in a traditional ox cart pulled by cattle to explore some local villages.

Eco-friendly luxury at Tri Hotel

First came the surroundings, then the hotel – although they make such a perfect match it’s hard to imagine one without the other. Set on Koggala Lake about 20 kilometres from Galle, Tri boasts 11 suites created to complement the natural world around them. Eco-friendly design elements go beyond solar power and local material – here, you’ll also find living walls, green roofs and edible gardens abundant with local fruit, herbs and spices, including cinnamon.

Settle down by the cantilevered pool or stretch out in the treetop yoga shala. For something more active, kayak on the lake, go temple hopping or visit the hotel’s private beach just a short drive away. At night tuck into locally sourced seafood and produce and enjoy a sense of living closer to nature.

Learn to cook sweet Korean treats

Sure enough, I find what appears to be a Parisian confectionery tucked among the fruit stands and chicken feet vendors. I ogle the rows of coloured bonbons and miniature cakes. There are pastel circles dipped in coconut, tiny flowers coated in jelly, white half-moons with delicate green stripes. Unlike your typical sweet treat, it’s all made of rice.

Tteok is traditional Korean rice cake. As ubiquitous as kimchi, it has a ceremonial weight pickled cabbage just can’t match. Tteok has been part of Korean culture for thousands of years. There are dozens of varieties to mark the journey from birth to death, each for a different life event or season.

Unlike the puffed-air frisbees I’m used to, Korean rice cake is dense and chewy. It clings to my fingers and pulls at my teeth like taffy. School children eat tteok before a big test to help the answers stick in their minds. But it’s also a celebratory food. Football-shaped songpyeon are eaten for the Chuseok holiday. White coins of garaetteok symbolise prosperity at Lunar New Year. My favourite is baekseolgi, a soft, spongy cake that celebrates a baby’s first hundred days.

Tteok used to be made in the home, but nowadays Koreans rely on tteok jibs to keep up with the revolving calendar of holidays. These specialty shops range from hole-in-the-wall kitchens to glossy storefronts. The cakes are made fresh to order and often include delivery. In South Korea’s convenience culture, there’s a tteok jib every few blocks.

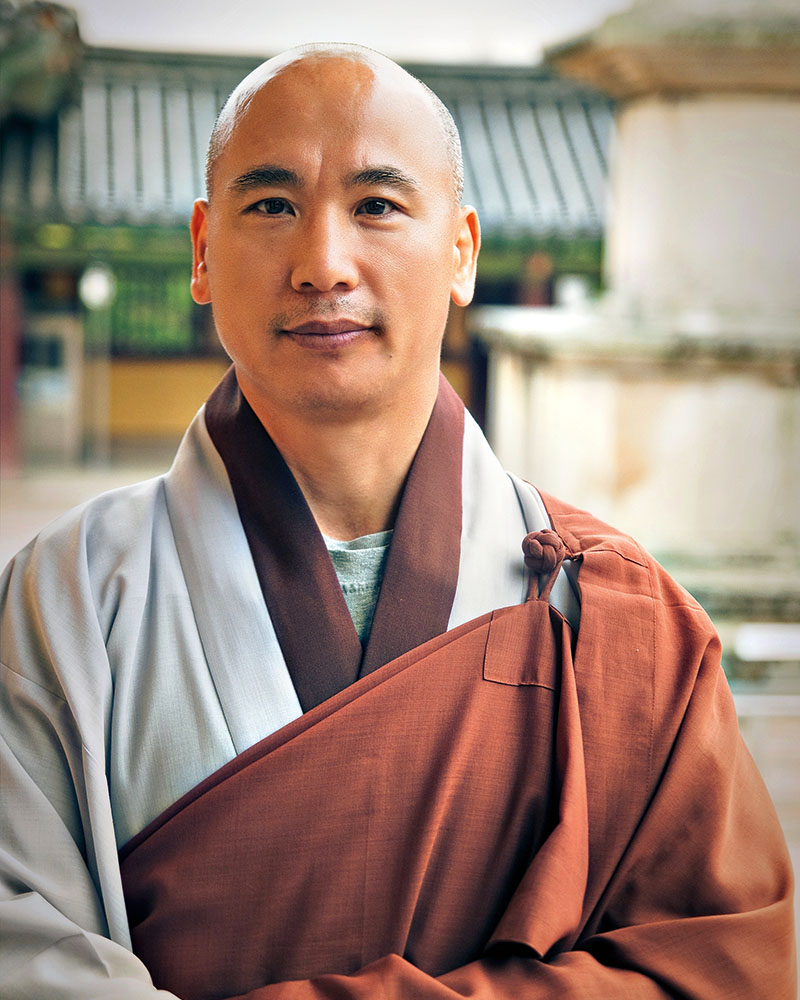

I head to Chungju’s Munhwa neighbourhood to meet Hwe Yeong Ju, a tteok chef and jib owner. She’s been making rice cake for 20 years, and the walls of her store are lined with photos and awards. One picture shows her smiling in a white chef’s toque, another in a traditional hanbok (dress). Below the frames is a display case of specialty gift boxes.

The packages are nearly as intricate as the sweets inside.

But my translator is distracted by the window display. “Oh, so delicious,” she whispers, pointing to sesame-dusted injeolmi tteok. A popular festival treat, injeolmi is labour intensive. Its thick, sticky texture is achieved by brute force pounding. In the old days, this was done with man-sized hammers or wooden treadle machines. Just making the rice flour involved stone grinders, massive mortars and pestles, and maybe an ox.

The process was so exhausting it became communal. Extended families worked together to make enough for each household.

I ask Mrs Ju how tteok making has changed, and she leads us to the kitchen. It’s all stainless steel and white tiles. Hefty machines take the floor space, and shiny steamer baskets line the walls. Every aspect of the process is done in-house. First, rice is soaked for six hours, then ground into flour. Most people haul their rice to a miller, but Mrs Ju has her own grinders. There’s an automatic sifter, a machine for pressing injeolmi, and even one that wraps pieces like chocolate bars.

The metal worktable blooms with roses. These too are made of tteok and will decorate a chocolate rice cake. Western tastes and aesthetics have become popular in South Korea, creating demand for fusion recipes, but traditional flavours, like red bean, are still the most popular. The shimmering colours come from natural ingredients: mugwort greens, sweet potato purples, rich pumpkin yellows.

When I ask Mrs Ju about tteok’s shift from home to jib, she cites the economy. The country experienced a massive upswing between the 1960s and ’90s. Within her lifetime, South Korea went from a third- to first-world nation. Rocketing growth had an impact in the kitchen.

“As the economy developed, housewives launched into the world and got jobs,” she says. There isn’t time to make all that rice cake these days, but that isn’t the only factor. “People think making tteok is difficult,” she adds. It’s a perception she’d like to change, so she teaches a tteok cooking course at the Chungju Women’s Center. The students are locals, mostly young mothers and brides-to-be. Among them, I felt like a less-impressive version of Julia Child in France: loud, foreign and way too tall. But enthusiasm overcomes the culture barrier.

I ask one young woman why she enrolled, and the others answer for her: “To help get a husband.” “To impress her future mother-in-law.”

We’re making my favourite, baekseolgi. For a baby’s hundred day party, the cake is pristinely white, but tonight we add sweet potatoes for colour and flavour. The recipe’s surprisingly straightforward. Add potato to the rice flour, sift and steam. Mrs Ju demonstrates a batch, then turns us loose. Muggy clouds roll off our steamers, giving the air a summer closeness. We wilt, fanning ourselves with recipe cards. But our teacher walks the tables in a crisp lab coat, lifting lids, tasting, adjusting, coaching. Tteok is as much art as science.

This is especially true with our homemade rice flour – it’s hard to get the moisture right. She rubs my mix between her fingers, then sluices in more water. She has me feel it. My fingers find a texture like grated parmesan cheese. It clumps when I squeeze it, and she smiles: perfect.

We use both purple and yellow sweet potatoes. Mrs Ju has us layer the colours in the steamer basket, so it cooks in stripes. Then she gives us a pro-tip: cut the tteok before steaming for clean, perfect pieces.

Afterward, we turn our baekseolgi out onto the table. The colours are Crayola bright, and the two-tone squares look like kitchen sponges. Mrs Ju offers plastic bags so we can take our triumph home. By the end of class there’s no need. We’ve eaten it all.

Makes 1 round cake

INGREDIENTS

4 cups tteok rice flour (also called glutinous rice flour, available at Asian grocery stores)

1/2 teaspoon salt

1 sweet potato, mashed

1/4 cup caster sugar

METHOD

Line the basket of a 30-centimetre steamer with cheesecloth or baking paper.

Combine rice flour and salt in a large bowl. Rub the mashed sweet potato into the rice flour with your fingers. Sift the mixture through a wire sieve.

The resulting powder should feel coarse, like grated parmesan cheese, and clump together when squeezed. If it doesn’t, add one tablespoon of cold water at a time. Rub it into the powder until you have the right texture.

Sift the powder a second time. Sprinkle in the sugar and mix gently.

Pour the powder into your steamer basket, and smooth the top. Cut the pieces you want, so they cook with clean edges. Steam for 20 minutes and turn out onto a plate to cool.

Tteok tastes best the first day, but it also freezes well. You can substitute squash or cocoa powder for sweet potato, as long as you adjust the moisture accordingly. Spices, nuts and dried fruit are delicious additions as well.

Korean craft-beer haven

Wander up a back alley in Seoul’s Garuso-gil district and enter Mikkeller, a minimalist craft-beer haven. Laden with bold colour, this stripped-back space is the spot to taste 30 craft beers from around the world. There’s an excellent selection of the company’s own beers, but there are also offerings from breweries like Evil Twin, To Øl and 8 Wired – all of them on tap. Slurp down glasses of tantalising drops with tongue-twisting names like Spontan Watermelon, Crooked Moon Tattoo Stockholm and Wit My Ex while admiring the modernist cartoons scattered around the walls.

Drawing on its Danish heritage (the venue’s one of several offshoots from a bar in Copenhagen that goes by the same name), the fit-out is simple and organic, with a dash of Korean cute – the perfect place to immerse yourself in Asia’s burgeoning craft beer scene.

Blondes, soju and serenity in South Korea

Seokguram Grotto is a holy place and now I’m holed up in it. I hitched, huffed and hiked out this way in the early hours to bask in the beauty of nature, cleanse my soul of the misgivings of Seoul and watch the sun rise. I came to see the understated side of the Land of the Morning Calm, but hours after it should have appeared I’m still waiting for the sun’s grand entrance.

Legends abound on the history of this ancient precipice. The most inspiring suggest that during the summer solstice when the light is right and the stars are aligned, the sun reflects off the Buddha’s third eye and illuminates the tomb of King Munmu in the East Sea. Munmu’s tomb protects Korea from Japanese invaders, the Buddha protects the tomb and a security guard protects the Buddha. With fables in my mind, I sit and watch the thunder clouds move from peak to peak, delivering their payload with unabated enthusiasm. I’m suddenly jealous of friends fond of the meditative life. Here I am in a place where serenity reigns, and all I can think of is moving on and exploring the countryside.

(

(